I think I’ve been overthinking this whole write-blog-posts-about-autism-during-Autism-ACCEPTANCE-Month thing. I think it is a product of my autism — tending towards very literal thinking and logical rigidity — which then triggered my pathological demand avoidance (PDA) and added much more hair pulling — and by hair, I mean beard — to the endeavor.

Instead of trying to explain autism and PDA from the ground up, I figure I should just say what I want to say about them when I want to say it since that is the way that I work best, and it is how I write just about every other blog post on Ye Olde Blogge. Yet, I can’t just write what I want to say; I have to tell you why I’m not doing it all.

Having a teenage daughter with PDA has taught me a lot about the disorder and about myself. It is like seeing yourself in a mirror that is showing you what might have happened had you wandered down a different path. It is frightening, humbling, and a little confusing. It is definitely much more difficult and painful to watch someone else go through the ordeals of not being able to comply with the expectations and norms of society even though you look like you orta be able to. It frequently breaks my heart, but this, too, is not what I want to write about except for maybe in a later blog post.

My Daughter’s Meltdowns

Today, I want to focus on a specific lesson that my daughter has taught me about PDA. After watching her meltdown and listening to her explanations of of her meltdowns and of what she experiences during her meltdowns, it occurs to me that a large part of the issue is her emotional response to the situation. Specifically, she is not experiencing a single dominate emotion but several equally strong emotions resulting in confusion and anxiety and the desire to stop everything until her emotions can sort themselves out.

“Hey, La Petite Fille, your social studies teacher wants you to watch the documentary, ’13th.’ That sounds fairly easy to do,” I suggested to her earlier this week when we were looking through her assignments for a task for her to do.

“No,” she said. “I can’t.”

“But, you watch lots of documentaries on the Internet. It should be right in your wheelhouse,” I argue hopefully.

“I CAN’T, dad,” she answers quietly.

“Okay,” I respond feeling a bit defeated, “but you’ve got to do something today. We’ve got to make some progress towards completing your assignments.”

“I CAN’T, dad!” she repeats sounding a little more desperate facing yet another morning of inaction and threatening to bleed into the afternoon making a day in which she gets nothing done.

“Look, you’ve got lots of assignments due. You’ve got to be productive, La Petite Fille.” I bite my tongue to keep myself from saying something like, ‘You’re not being reasonable,’ which would be totally counterproductive.

“I don’t want to be productive,” she retorts winding up. “I don’t care if I pass school! I don’t care about my future!” She is now entering full meltdown territory.

“What are you feeling right now?” I ask her as her meltdown deepens trying to get her to focus on the moment.

“I DON’T KNOW how I feel!” she’ll exclaims with increasing hysteria, the opposite of what I want.

“Are you feeling angry?” I suggest still hoping.

“I feel lots of things!” she answers looking wild and sounding out of control.

“Maybe, we should do something to help you calm down,” I say realizing that nothing is really helpful can be done right now.

“I DON’T KNOW what I should do!” she lamented. “I don’t know how to calm down!” And, my heart begins to break because I understand that I cannot help her right now. She is suffering terribly, and there is nothing I can do to alleviate that suffering. In fact, it only seems like I can make it worse.

Eventually, she decides to go lay down for a bit. After she has recovered from the meltdown, she is quite productive and completes an assignment without further argument.

My autistic mind that focuses on observation and the development of rules that govern the situation I’m observing, begins to wonder about the role of emotions in her meltdowns and how she decides what she’ll be doing at any given moment of time.

The Intrapersonal Role of Emotions

Most of us think of emotions as reflecting the internal feeling-state that we are in. We describe ourselves as happy or sad or angry or some other emotion often conflating them with feelings of physical sensations such as feeling hungry or tired. But, they are more than that. They serve a complex function in mammalian life. They play important roles in both our intra and interpersonal interactions as well as in our larger social activities.

Our intrapersonal emotional experience helps us respond to our environment by acting as a kind of shorthand. Instead of needing to consider every possible response to a situation — do I throw the leftover mashed potatoes away or heat them up for lunch today? — we know “instinctively” how to act. If they smell sour or are growing mold, they get thrown away. If not, we should have them for lunch. We react quickly and without much thought.

In that sense, our emotions are always on reacting to our perceptions of our environment. They guide our behavior depending on how strongly we’re reacting. In some senses it is this intrapersonal interaction with our emotions that is most important here. When our environment changes, we query our emotions, get a response, and react. Without that intrapersonal emotional response, it would be quite impossible to make decisions.

Damasio’s Case Study of Elliot

A well known case study by the influential neuroscientist, Antonio Damasio illustrates this point. This case study was reported in his book Descartes’ Error. In it he reports on a patient of his that he called, Elliot. Elliot had had a brain tumor removed, and the resulting changes in behavior brought him to Damasio.

Before the removal of the tumor, Elliot was “normal.” He had a stable family life and a good job. He even excelled at what he did. Afterward, though his life “fell apart.” Eventually, he lost his job, got divorced, filed for bankruptcy.

Yet, he still had all of his cognitive abilities. He had all of his memories, language skills, personality, charm, diligence. Very little had changed in him except his ability to make decisions. He couldn’t make any sort of decision even one so trivial as his next appointment would be. He spent his time trying to figure out what was the best time by evaluating all the possible metrics that would make a time preferable. He couldn’t decide whether to drive to the appointment or take public transportation. He couldn’t decide anything. When he did decide, it usually ended in disaster.

Damasio concluded that “…the cold-bloodedness of Elliot’s reasoning prevented him from assigning different values to different option and made his decision-making landscape hopelessly flat.”

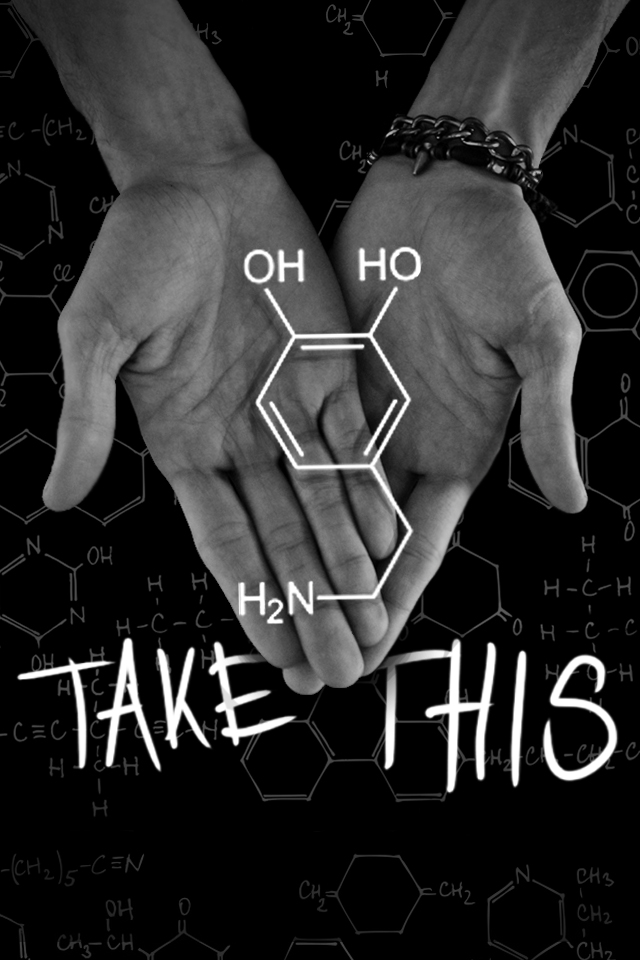

Damasio proposed a theory that would explain such a situation: the somatic marker hypothesis. When faced with a decision, we generate an emotion or feeling about the success or failure of the choice. Sometimes we are aware of those feelings and sometimes not, but they still influence our behavior and mental processes, nonetheless. Without those somatic markers of liking having the appointment on Monday over Tuesday and in the afternoon over in the morning, we wouldn’t be able to decide when to go visit the doctor. There may or may not be a compelling logical reason for making those choices, but we make them anyway and are happy about it.

The Brain and Emotions

The removal of Elliot’s tumor necessitated destroying a connection between the emotional parts of his brain and the thinking parts of his brain. Emotions are processed in the limbic system, an older set of brain structures located near the center of the brain beneath the cerebral cortex. The thinking parts of the brain are located in the newest parts of the brain known as the prefrontal lobe just over the eyes in the cerebral cortex. In essence, the thinking part of his brain was no longer receiving the signals from the emotional part of his brain, so he could no longer make decisions based on those signals.

I think that my daughter and I both have similar experiences of our emotions. When something changes in our environment and we query the emotional parts of our brain for a response, instead of getting no emotional response as Elliot did or just one or two responses as most people do, we get all of the emotions. There is a flood of emotions. You get both like and don’t like in equal amounts.

We are literally trying to do everything at once and nothing is clear. Faced with such an overwhelming and confusing situation, we do the only rational thing: we try and get the world to stop. Everyone should stop asking us questions. We should not do anything.

The world seems very dangerous under these circumstances. Worse, we cannot focus on a single danger, it just feels like it is out of control and anything can happen. It is dangerous. Withdrawing from the world to reduce the emotional overload makes sense. Pathological demand avoidance (PDA), then, is based on the inability of the emotional brain to react with a single or manageable number of emotions. There is a disconnect in the development of the emotional part of the brain allowing for the usual emotional reaction. Without this clear emotional reaction, no decisions can be made and the only way to feel safe is to withdraw to get the world to stop.

If you enjoyed this explanation of pathological demand avoidance, join our email list.

Image Attribution

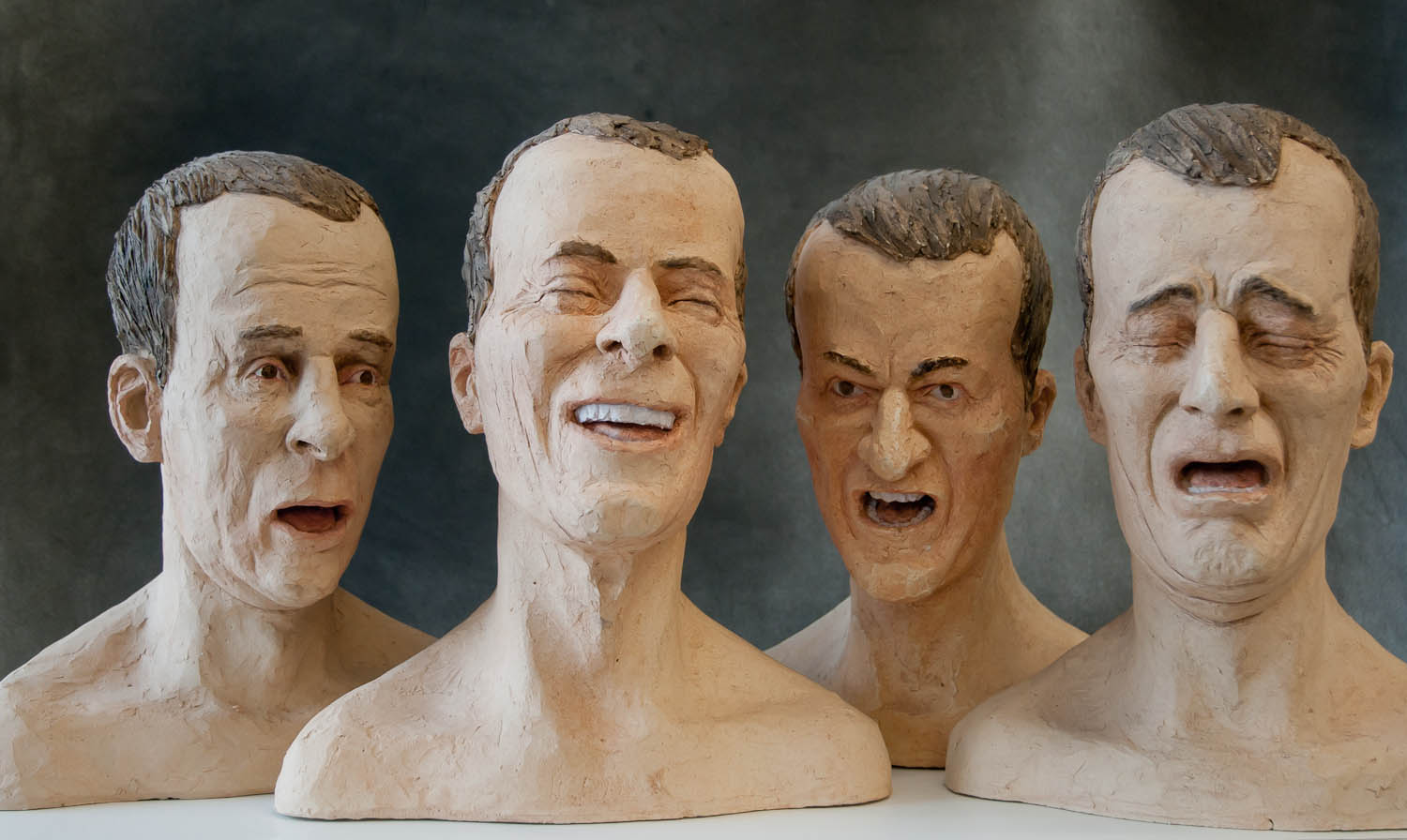

“overwhelmed” by madamepsychosis is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Categories: Autism

Reblogged this on cabbagesandkings524 and commented:

Calico Jack – Decisions, decisions

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have to say that my therapeutic training (back in the 80s) included no mention of PAD. Now, I’m thinking about various clients, patients, and others who had meltdowns and/or difficulty making decisions or who tended to withdraw (including using alcohol and other depressants), and wondering how much part some degree of PAD might have been playing. And then, I think of the people who appear to be simply unable to process and respond to information about things like COVID and climate change except by, not so much denying them, but avoiding the subject entirely (Like your daughter saying, “I CAN’T!”.), especially when confronted with contradictory narratives.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Howdy Bob!

PDA is a relatively recent and, as yet, not completely accepted condition. It is referred to as a profile in the autism spectrum describing a set of symptomatology. I believe it was originated in the 1980’s by the British psychologist, Elizabeth Newson. As such, it is more widely accepted in the UK.

When I look back at my career before I knew what it was in the mid-aughts, I realize that there were both students and clients that it describes. The test for knowing whether you are dealing with a PDA’er is how often you respond to that person with, “But it would be so much easier if you would just do X!”

I could see people with PDA refusing #COVID19, especially in certain circumstances.

Huzzah!

Jack

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is so much talk about “overthinking”, that I suspect PDA or tendencies toward it are far more common than might be thought.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Every mental health symptom is a normal reaction on steroids that takes over a life. We all have things that we’ll refuse to do out right because it strikes us as wrong. However, given the veritable explosion in autism diagnoses, I suspect we’ve had far more autism in society than we really knew.

Jack

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another way to put it is that our official definition of “Normative” may be wrong, which is likely since it is based in the assumption of rationality, and we are not very rational.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Howdy Bob!

That certainly has been the problem in most microeconomic theories. We don’t act ver rationally when it comes to making economic decisions and that probably generalizes to all decisions.

Damasio’s somatic marker hypothesis could probably be extended to many of our decisions. An interesting study would be to apply it to a crowded presidential field. You could hook participants up to the galvanic skin monitor and evaluate pictures of possible candidates asking whether they seem very presidential. You could see if the galvanic response corresponded to the performance of the candidate in the primary election. For example, many people convinced themselves that Sanders could win, but I bet if you did the somatic marker test with them, you’d get a no not presidential response. The same with Marco Rubio, Lindsey Graham, John Hickenlooper, and other candidates. It would be interesting to see how people felt about female candidates.

Otherwise norms are pretty poorly defined as in specific behaviors, but we all know when they’ve been violated… at least, for people in our sub-culture.

Huzzah!

Jack

LikeLiked by 1 person

If Trump supporters had been involved in such a test, would they have seen him as “presidential”, or were they looking for someone the very opposite of the usual definition of that description? I suspect the latter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Howdy Bob!

That would’ve been an interesting test, too, because when applied to the Iowa gambling task, where participants were told to draw cards from two decks one stacked in their favor and one stacked against them and then begin to predict when the cards would favor them and when they wouldn’t. The galvanic skin test showed that they knew the deck stacked against them was likely to hurt them after the first five cards were drawn, but didn’t start predicting it until the twentieth card. I wonder if the supporters would’ve voiced support but the test reveal otherwise. I think it very well might have. It wouldn’t stop people from voting for someone or donating to them, but it would reveal their “true” thoughts about whether they were qualified for or could handle the job.

Huzzah!

Jack

LikeLiked by 1 person

And, if what they really wanted was something completely different, the should have stuck with Monty Python reruns.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve always maintained that Monty Python didn’t do much more than just record the things that happened around them. At least that was my impression from my 80’s trip through England. It all seemed like one long weird Python skit. There certainly is plenty of Pythonesque material going on on the conservative end of the spectrum.

There was an excellent Monty Python documentary on Netflix for a while. It may have been moved off of their rotation, though.

Huzzah!

Jack

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s pretty accurate.

LikeLiked by 1 person